December 14, 2018 | Kathryn Tworkoski, PhD, RAC, Senior Clinical Research Scientist │ Regulatory Affairs, Medical Writing, Drug Development Consulting

Long-time readers of this blog will recall (with great enthusiasm, I’m sure) our previous posts on rare diseases, INDs, preparation for pre-IND meetings, and the submission and maintenance of INDs. But in October 2018, the FDA released new draft guidance outlining best practices for early drug development and pre-IND meetings for rare diseases. Given the near-perfect cross-over potential, we thought this was a sign that it was time to review the guidance, as well as rare diseases as a whole. So in the interest of appeasing the fates, let’s get this show on the road!

Overview of rare diseases

Since we haven’t written about rare diseases for a few years, it’s probably worth revisiting the state of the field. As you may recall, rare diseases are defined as diseases or disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 individuals in the United States. Many rare diseases are caused by inherited genetic mutations and it is not uncommon for rare diseases to have a serious impact on an individual’s quality of life, or to even be life‑threatening. As an unfortunate consequence, it is estimated that up to two‑thirds of the individuals living with a rare disease are children.

Drugs that are used to treat rare diseases are called orphan drugs. Since drugs may be approved for multiple indications (including rare diseases and non-rare diseases), it can be difficult to track the number of FDA‑approved orphan drugs. However, if we focus our attention on new molecular entities (NMEs; which are slightly easier to track), we can see that over the past 5 years (from 2013-2017), roughly 40% of the FDA‑approved NMEs were orphan drugs. That’s a significant proportion!

The number of orphan drug approvals is perhaps reflective of the size of the rare disease population. Although individual rare diseases are uncommon, it is estimated that up to 30 million individuals in the United States are living with a rare disease. That’s roughly 1 in 10 Americans! And although the market for orphan drugs is (relatively) small, it’s still significant; it’s estimated that orphan drugs accounted for approximately 8% of total drug sales in the United States in 2016, and approximately 10% of total drug sales in 2017.

Unfortunately, it’s also estimated that only 5% of rare diseases have treatments. So there is still quite a ways to go in terms of developing treatments for these diseases.

New guidance

Given the high percentage of recently approved orphan drugs and the need to develop more orphan drugs, it’s not surprising that the FDA is interested in streamlining the development processes. To that end, the FDA has recently released a series of draft guidances pertaining to orphan drugs. In July of 2018, the FDA released draft guidances entitled “Slowly Progressive, Low-Prevalence Rare Diseases with Substrate Deposition That Results from Single Enzyme Defects: Providing Evidence of Effectiveness for Replacement or Corrective Therapies” and “Human Gene Therapy for Rare Diseases.” As you would expect, these guidances provide insight into either the development of specific types of orphan drugs or orphan drugs for specific types of rare diseases.

More recently, in October 2018, the FDA released another draft guidance called “Rare Diseases: Early Drug Development and the Role of Pre-IND Meetings.” Unlike the previous two guidances, this document is meant to be applicable to the development of all rare diseases.

As you many know, an IND is a collection of documents that allows you to start clinical trials in human subjects (and technically gives you permission to ship experimental drugs across state lines). A pre-IND meeting is a chance for a Sponsor to seek the FDA’s opinion on their clinical program, as well as the nonclinical studies and CMC information supporting the clinical program, before officially submitting the IND. Pre‑IND meetings are especially useful for orphan drugs, since there tends to be a bit more uncertainty involving rare diseases than there is in more prevalent maladies.

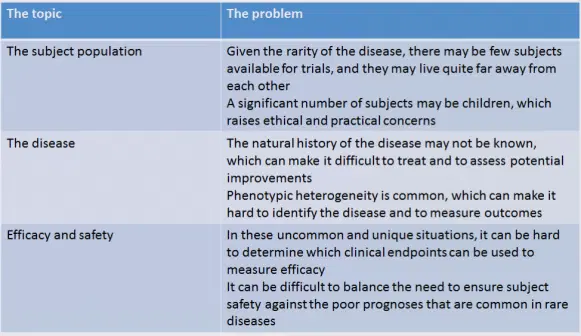

In the draft guidance, the FDA touches on several issues that are unique to orphan drugs, and which may therefore require special consideration. Although there are many potential difficulties that may arise during the development of an orphan drug, I’ve summarized some of the bigger concerns in the table below.

To address the small number of subjects that may be available for clinical trials, the FDA notes that clinical studies may be conducted in healthy subjects to support clinical safety and pharmacology claims. The FDA states that they have “no specified minimum number” of subjects that are required to “establish drug safety and efficacy.” The FDA also suggests the use of platform studies, in which multiple treatments may be evaluated simultaneously.

Since many rare diseases occur in children, the FDA advocates initiating pediatric studies as soon as possible. In fact, it is suggested that the pre-IND meeting may be an ideal place to determine when pediatric studies may be initiated.

Given the potential uncertainty and/or variability associated with rare diseases, the FDA notes that it is important to carefully select nonclinical models so that they accurately reflect the disease under consideration. In some instances, nonclinical models may actually be engineered not only to establish drug safety and mechanisms of action, but also to inform the anticipated disease pathology in humans. The FDA states that it will “exercise flexibility” in considering the type and volume of nonclinical data that are needed, as well as the time at which these data are obtained during the developmental program.

Since rare diseases are commonly caused by genetic mutations, and since phenotypic heterogeneity is common, companion diagnostics are frequently used to determine whether a specific orphan drug would be effective in a given rare disease. The FDA suggests getting feedback on these diagnostics as soon as possible (during a pre‑IND meeting, for example!) to ensure that the tests are accurate and that they successfully identify an appropriate subset of patients for treatment.

When determining if an orphan drug is safe and effective for use in humans, the FDA uses “the broadest possible scientific judgement.” The FDA explicitly states that given the life-threatening nature of rare diseases, a greater level of risk may be acceptable for the treatment of rare diseases, relative to other diseases. The FDA considers the seriousness of the disease, and the need to identify a treatment for the orphan disease in question. The FDA may also consider which clinical endpoints are needed to determine if the orphan drug is working, since it is uncommon for a rare disease to have an established precedent for establishing efficacy. Together, these considerations can feed directly into several expedited approval pathways for orphan drugs (see below).

Incentives for orphan drugs

Like other drugs, orphan drugs are eligible for FDA expedited approval processes: fast track, breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, and priority review. But due to the nature of rare diseases, orphan drugs are far more likely to obtain at least 1 form of expedited review, compared to non-orphan drugs. Over the past 3 years combined (2015-2017), approximately 90% of the NMEs approved by the FDA as orphan drugs were given some type of expedited review.

As we discussed earlier, the natural history of orphan drugs is not always known, and it can be difficult to know which clinical endpoints are good indicators of therapeutic efficacy. So perhaps it’s not surprising that orphan drugs are associated with accelerated approval, where a surrogate endpoint is used to measure clinical benefit. For each of the past 3 years, the FDA granted accelerated approval to 6 NMEs. And each year, 5 of those 6 accelerated approvals were given to orphan drugs.

In addition to the expedited approval pathways, there are other incentives for developing orphan drugs. For instance, Sponsors can waive the marketing application fees for an orphan drug and approved orphan drugs receive 7 years of market exclusivity. There are also several grant programs (e.g., orphan products grants, pediatric devise consortia grants, and humanitarian use device grants) which may be used to offset the cost of clinical development.

Of note, one of the key incentives for orphan drug development was recently amended. The original Orphan Drug Act of 1983 allowed Sponsors who developed an orphan drug to receive a tax credit equal to 50% of the clinical trial expenditures. However, during the recent tax code overhaul in 2017, this tax credit was reduced from 50% to 25%. While a 25% tax cut is still a notable financial benefit, it remains to be seen how this alteration will impact orphan drug development in the long run.

All in all

Looking ahead, there are a few signs that orphan drug development programs may change in the coming years. We’ve mentioned that the tax credit for orphan drugs was recently changed, and there are concerns that the promised 7-year market exclusivity may restrict the development of improved therapies and allow for exorbitant prices to be charged for approved orphan drugs. On the other side of the coin, some people believe that exclusivity is a necessary incentive to drive orphan drug development. With that in mind, the OPEN Act was introduced in 2017, which would add a 6-month extension onto the exclusivity period of a previously approved drug that was also approved to treat a rare disease. Although the OPEN Act has not progressed in the US House of Representatives, in early 2018, the FDA Commissioner indicated that he was open to reconsidering the incentives used to promote orphan drug development.

There is also interest in refining the way in which orphan drugs are reviewed and approved. In September 2018, to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the orphan drug act, it was proposed that the FDA establish a Rare Disease Center of Excellence to facilitate the development and review of orphan drugs. In October of 2018, a senate subcommittee hearing was held to discuss the challenges faced by orphan drugs. Physicians, advocacy groups, and pharmaceutical companies suggested the use of alternative and/or adaptive trial designs to improve subject enrollment and to facilitate the measurement of clinical outcomes. Speakers also suggested facilitating orphan drug approval across different geographic regions, and creating databases to compile rare disease data.

Although it is not entirely certain what the future holds for orphan drugs, it does seem clear that the interest in developing orphan drugs, and in facilitating the development process, is only going to increase. If you have any questions about orphan drug development, don’t hesitate to contact us: we’re happy to help! And if you found this post interesting, you can always get more information by following us on LinkedIn.

Category: Regulatory Affairs, Medical Writing, Drug Development Consulting

Keywords: orphan drug, rare disease, IND

Other Posts You Might Like: