October 30, 2019 | Brandi Schuster, PhD, Clinical Research Scientist | Medical Writing Services

So you’ve decided to begin a career in medical writing – congratulations! Now what?

It may be scary leaving the comfort of your lab and pipettes, and medical writing may seem very different from academia, but you are more equipped for this transition than you may realize! (No, I’m not referring to your pipettes…)

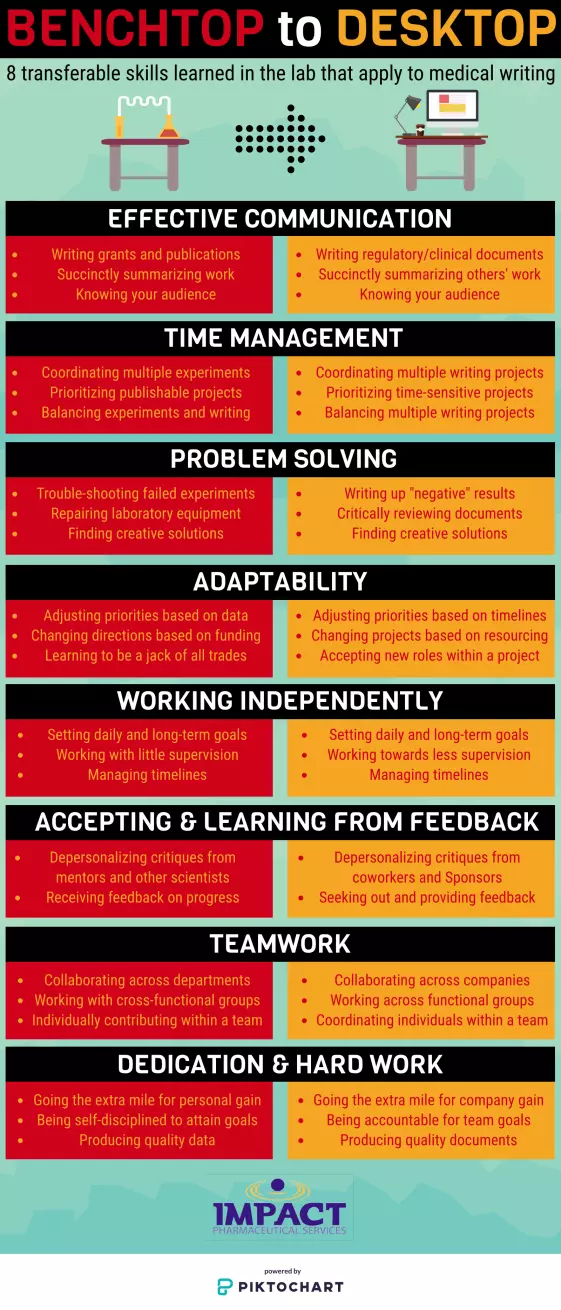

Today, graduate students have access to several resources to help them break into the field of medical writing. While I encourage you to check these out, I also want to point out that you’re already learning valuable lessons at the bench that are applicable to any new job or work environment, including medical writing.

This blog post outlines 8 skills that are transferable from the benchtop to the desktop. As Leah Busque stated, “People with highly transferable skills may be specialists in certain areas, but they’re also incredible generalists – something businesses that want to grow need.”

1. Effective Communication

Effective written communication may be the most important transferable skill you can bring to medical writing. Fortunately, life in the lab offers many opportunities to hone your writing skills.

Preparing grant applications, manuscripts for publication, your own dissertation, or even your lab’s website are all ways you are learning to communicate effectively. And each of these experiences is teaching you to write for different audiences – whether those be funding agencies, journal reviewers, your graduate committee, or fellow researchers at a poster presentation.

As medical writers, we use similar communication skills to prepare documents for different purposes and varying audiences.

Sometimes we are asked to write similar information within different contexts (eg, writing a clinical study report [CSR] and Investigator’s Brochure for the same drug). Being able to succinctly summarize ideas and anticipate your audience’s questions are skills that scientists use on a daily basis that are directly transferable to medical writing.

Bottom line: Effective communication is about exchanging information at the right time and in the right way for the intended audience.

2. Time Management

Most of us have learned the importance (and necessity) of effectively managing our time in the lab. Whether it’s performing DNA extractions during cell incubations or setting up a reaction while a plate reader goes through your next stack, you have likely worked on multiple experiments simultaneously. You have also likely coordinated experiments with writing time – manuscripts do not write themselves!

Medical writers (especially those at contract research organizations [CROs]) rely on their time management skills when working on multiple projects at once to increase productivity. Instead of buzzing around between instruments, we are coordinating multiple project timelines with an array of teams. While learning how to juggle multiple tasks at one time is important for both bench science and medical writing, knowing your limits is equally important. Work quality can be sacrificed when you overextend yourself with multitasking. Sometimes, with bench work and writing, multitasking can be efficient; other times it is best to focus on one thing at a time, or simplify tasks that you cannot eliminate.

Bottom line: Time management is about finding a balance between productivity and work quality.

3. Problem Solving

Although your diploma may say that you have a PhD in microbiology or biochemistry, ultimately you have been trained to be a professional critical thinker. A crucial part of thinking critically is problem solving. From trouble‑shooting failed experiments to repairing broken laboratory equipment (because that successful S10 grant application you wrote didn’t cover the purchase of a service plan…), you are equipped to solve complex problems that require immediate answers. Often times, problem solving takes the form of knowing who in the lab you need to ask for help.

As medical writers, our problems look a bit different; perhaps we’re writing up “negative” results in a CSR for a clinical study that didn’t meet any of its endpoints, deciphering a new style guide or template, or critically reviewing documents. Regardless, the same problem-solving skills that are necessary for finding creative solutions in the lab are directly transferable to a career in medical writing. We need to know who to ask or what document or website to look up to get necessary information for our writing assignments.

Bottom line: Problem solving is not about knowing the answer, but knowing how to find the answer.

4. Adaptability

Have you ever walked up to a common-use instrument to realize that the only available time slots are either before 8:00 am or after 4:00 pm? If so, then you’ve likely practiced adaptability in the lab. Adaptability is also necessary for adjusting priorities based on unexpected data results or switching your research focus based on changes in project funding.

In the lab, you may have learned to become a jack of all trades in order to adjust to shifting priorities and move on to the next experiment. Much like bench scientists, medical writers must be adaptable to a continually changing environment.

Project timelines can change frequently based on clinical and statistical analysis activities. Changes to industry and regulatory landscapes often result in sponsors changing their program’s priorities. Resourcing to projects can also change as a result of these timeline and priority changes.

Additionally, as medical writers, we adjust to accepting new roles within a project – one day we may be writing a document, the next day QCing a different document, and then the next day reviewing another document. Even within the same document, medical writers take on different roles – from synthesizing and summarizing background information to interpreting and discussing data, to fielding feedback from the Sponsor and helping them develop strategic arguments. The flexibility you learned as a bench scientist is directly transferable to medical writing.

Bottom line: Adaptability is about being flexible and successfully navigating change.

5. Working Independently

By the end of your graduate school experience, you have become an expert in your specific area of research. That process of becoming an expert likely involved a lot of independent work. Deadlines can be nebulous in graduate school. Essentially, you have time on the order of years (perhaps up to 6 or 7 years) to work towards one long-term goal – your dissertation defense. But getting to that point requires focus, short-term goals, and working with little supervision.

As medical writers, we still set short- and long-term goals, but on a much faster timescale – generally on the order of months or weeks, and sometimes even days. There is quite the shift from leaving the bench as an expert in your field to entering the world of medical writing as the newbie. However, the skills you have honed as an independent researcher in the lab will be directly transferable to medical writing as you move towards needing less supervision and taking more initiative with projects.

Bottom line: Working independently is about taking initiative to produce high-quality work.

6. Accepting and Learning From Feedback

Receiving feedback, whether positive or constructive, is an excellent way to learn and grow in any position. It can be easy or difficult to hear depending on the style of its delivery, so an essential tool for accepting and learning from feedback is depersonalization. If you’ve made it through graduate school with a semi-firm grasp on your sanity, then you have probably learned the value in depersonalizing feedback from both those within and outside of your lab.

Separating yourself from a project allows you to gain perspective when listening to feedback and address the underlying issue. And it’s important to recognize that the underlying issue may or may not relate to something you have control over. Both scientists and medical writers can find themselves in positions where they have limited information yet need to produce high-quality work.

For example, the methods section of the manuscript you’re modeling your experiments after may be vague or faulty – failed experiments or slow progress for reasons outside of your control could result in harsh feedback. Similarly, sometimes when we pull text from a protocol or statistical analysis plan into a CSR, we receive feedback that the information doesn’t make sense or is no longer correct. This feedback may be valid and should be accounted for in the CSR, but we should not feel personally at fault.

As medical writers, our documents are reviewed several times by different teams including multiple rounds of QC and for scientific merit internally or by the Sponsor. Learning to listen to, evaluate, and accept constructive feedback is essential for growth in any profession. Here at IMPACT, we take a proactive approach to professional development as medical writers by seeking out constructive feedback on a regular basis.

Bottom line: Accepting and learning from feedback is about actively listening, gaining perspective, and implementing necessary changes.

7. Teamwork

Scientific progress and academic collaboration go hand-in-hand. As a bench scientist, you have likely worked with scientists from other labs, departments, or universities. Some of these collaborations may have been cross‑functional with people from varying disciplines and areas of expertise. Working with these multidisciplinary groups has developed your teamwork skills, something medical writers rely on daily.

As medical writers, we are constantly interfacing with individuals from varying expertise within a project – from statisticians to patient safety representatives and pharmacology leads. Unlike graduate school, where you mostly contribute individually to a team, medical writing requires coordinating individuals within a team – external teams with a Sponsor as well as internal teams.

It often takes a team of medical writers to tackle a large project, particularly if it has multiple components (eg, New Drug Applications). Medical writers within a team may have different strengths or interests in terms of therapeutic areas, drug developmental phases, document types, or sections within documents (ie, safety vs efficacy vs pharmacokinetics). By working together, we can leverage these strengths to produce a high-quality document or set of documents. At IMPACT, we also promote teamwork outside of our usual projects through company initiatives like Making an IMPACT.

Bottom line: Teamwork is about combining individual strengths to work towards a common goal.

8. Dedication and Hard Work

Graduate students are no strangers to dedication and hard work! A lot of self-discipline is required to attain a graduate degree. And dedication is a requirement for collecting high-quality and reliable data in the lab. However, when making the transition from graduate school into medical writing, there is a shift from prioritizing self-serving goals to company goals. For example, while working on your dissertation research, you may have the goal to publish a manuscript in a specific journal – you decide which and how many experiments to perform (with the help of mentors) and you decide what the final manuscript will look like.

As medical writers, the end goal for a project is assigned to us based on company and sponsor needs and priorities. At a CRO such as IMPACT, we partner with sponsors with the goal of producing high‑quality documents that accurately summarize others’ work. Self-discipline and time management are necessary to achieve these company goals and to make progress towards personal goals (such as professional development objectives) in parallel.

Working hard towards company goals while making progress towards personal goals often means working smart to avoid burnout. To land your first medical writing job requires hard work and dedication, but you have likely been honing good work ethic skills every day in the lab.

Bottom line: Dedication and hard work are about making a commitment to produce a high-quality end product.

If you are interested in becoming a medical writer, please check out our Medical Writing Fellowship program! IMPACT is an exciting, small CRO whose team has expertise in medical writing, regulatory affairs/operations, early phase clinical trial management, and drug development consulting. If you’d like to learn more about Syner-G, don’t hesitate to contact us!

![]()

Category: Medical Writing Services

Keywords: medical writing, regulatory writing, career transition, transferrable skills, fellowship