February 16, 2018 | Kathryn Tworkoski, PhD, RAC | Clinical Research Scientist II | Regulatory Affairs, Drug Development Consulting

Introducing a new therapeutic agent to human patients can be simultaneously exciting and nerve-wracking. Over the years, we’ve had a lot of questions about the best way to prepare for an Investigational New Drug (IND) submission. So we’ve decided to tackle those questions in a series of blog posts. In this introductory post, we’re going to focus on some background information that will help explain the overall purpose and requirements of an IND.

Let’s start with . . .

What is an IND?

Technically speaking, an IND provides an exemption from the New Drug Application (NDA) regulations, allowing you to ship your investigational drug across state lines in order to conduct clinical trials. The FDA formally defines INDs and their requirements in 21 CFR 312.

An IND is submitted by a Sponsor, who assumes responsibility for initiating and overseeing a clinical investigation (study) or a series of clinical investigations. Sponsors are usually multi-person organizations such as pharmaceutical companies, academic groups, or government agencies. Occasionally, however, a Sponsor can be a single individual who initiates and conducts a clinical investigation with an unapproved drug (sometimes called a “Sponsor-Investigator;” read on for more information!).

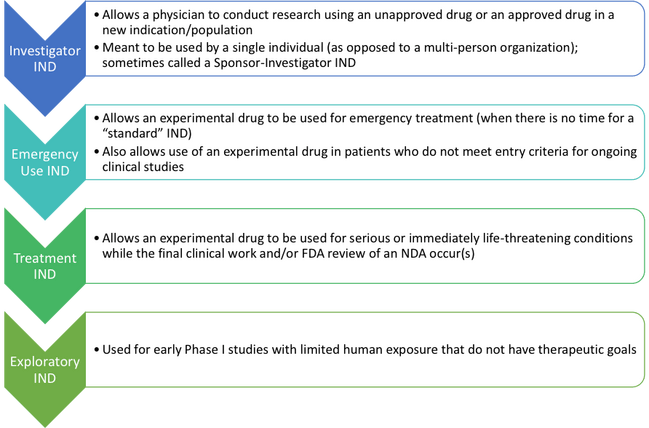

There are two basic types of INDs: commercial and research. As you would expect, commercial INDs are used when the ultimate goal is to seek approval to market a new drug, while research (or “noncommercial”) INDs are geared towards advancing scientific knowledge. In addition, there are several special subclasses of INDs (Investigator, Emergency Use, Treatment, and Exploratory) that are described below.

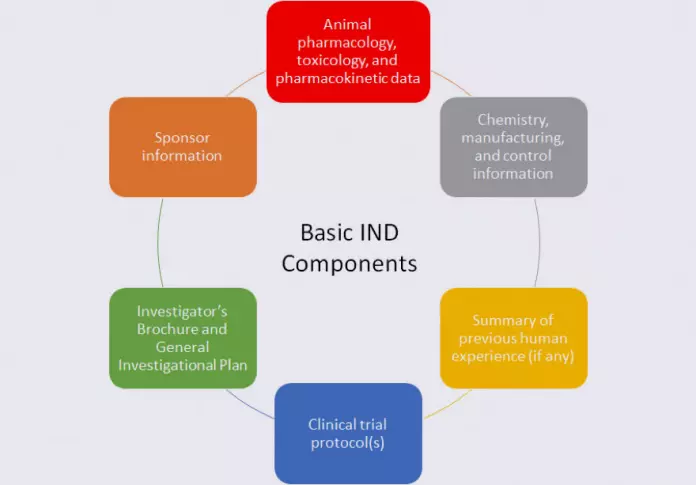

Regardless of the IND type, an IND generally contains several basic types of information, as described below:

Specifically, the animal data submitted in the IND, as well as the chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) information, must provide adequate assurance that it is safe to conduct clinical trials with the drug. The General Investigation Plan gives the FDA perspective on the drug development program, and the Investigator’s Brochure serves as a reference for Investigators in clinical trials and summarizes the information known about the investigational drug. The clinical protocol(s) provide the FDA with specific information on who will be exposed to the investigational drug, how many people will be exposed, the dose of drug used, and the duration of exposure.

For more information on the required content and format of specific IND components, refer to 21 CFR 312.23.

Now that we’ve established the basics of what an IND is, let’s move on to . . .

Related Articles: Four Top Roadblocks to Successful IND Applications and How to Overcome Them

What does the life of an IND look like?

Once an initial IND application is submitted, the FDA has 30 calendar days to review it. If a clinical hold appears to be warranted, the FDA will notify the Sponsor immediately during this 30-day window. But since IND applications are not formally approved, the FDA might not provide feedback to the Sponsor if there are no concerns surrounding the IND. If the Sponsor does not hear from the FDA within 30 days, the IND goes into effect (becomes “active”).

After an IND goes into effect, the Sponsor is allowed to proceed with their clinical program. However, if the Sponsor has not heard from the FDA, we still recommend that the Sponsor check in with their FDA project manager before starting clinical trials. Doing so can prevent bad news from popping up unexpectedly, and can preclude the need to put a clinical program on hold right after the program is initiated.

It’s important to remember that an IND is a “living application” (or set of documents); it needs to be maintained by the Sponsor in an “active state.” This is accomplished by submitting required amendments to the IND as the development program progresses through the well-known phases. Additionally, IND annual progress reports need to be submitted each year (within 60 days of the date that the IND went into effect). An IND is also updated outside of the annual report window with items such as important clinical/nonclinical data, new protocols, expedited safety reporting, and major manufacturing changes.

Once an NDA is approved, the associated IND is typically closed. Alternatively, if the Sponsor plans to run additional clinical trials under the IND, the Sponsor may elect to keep the IND open. It is, however, important to remember that as long as an IND is open (or “active”), the FDA will expect to see annual reports for that IND (in addition to any NDA submissions, including NDA annual reports).

Which brings us to the all-important question . . .

When do I need an IND?

According to the 21 CFR 312 regulations, an IND is needed for human studies if all of the following conditions are met:

- The research involves a drug (as defined in the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act).

- The research is a clinical investigation (as defined in the IND regulations [21 CFR 312.3]).

- The clinical investigation is not otherwise exempt from the IND requirements.

Although it is often very clear whether an IND is required to conduct a clinical trial, there is sometimes room for doubt. And given their workload, the FDA would actually prefer that you do not submit an IND application to them if one is not required! Several of the more common studies that may be IND-exempt (and the criteria that must be met for exemption) are described in the table below:

| Study Features | Criteria That Must Be Met To Avoid Filing An IND |

| Marketed drug | Drug is legally marketed in the US Study will not support new indication or significant labelling change Study will not promote or commercialize the drug Study does not increase risk associated with the drug Study will not support significant advertising change (for a prescription drugs) Study complies with IRB and informed consent requirements |

| Bioavailability or bioequivalence | Drug is not a new chemical entity, is not radioactive, and is not cytotoxic Dose is within range specified by approved labeling Study complies with IRB and informed consent requirements Sponsor meets requirements for test sample retention and safety reporting |

| Radioactive isotopes | Study for basic research (not diagnostic/therapeutic and does not examine safety/efficacy of drug) Drug use is approved by a Radioactive Drug Research Committee Dose is not known to have pharmacological effect in humans The amount of radiation used is minimized as much as possible |

| Cold isotopes | Study obtains basic information on metabolism, physiology, or biochemistry Study does not have diagnostic, therapeutic, or preventative aims Dose is not known to have pharmacological effect in humans Study complies with IRB and informed consent requirements Isotope meets relevant quality standards |

| Dietary supplement | Study observes effects on structure/function of body (no therapeutic purpose) |

If you think that your study may not require an IND, check out the September 2013 FDA guidance entitled “Investigational New Drug Applications (INDs) — Determining Whether Human Research Studies Can Be Conducted Without an IND.”

Stay tuned!

And there you have it; a very quick overview of INDs and their submission requirements. If you found this post helpful, keep an eye out for our upcoming blogs on pre-IND activities/meetings and on the submission of an initial IND. And as always, please contact us if you have any questions or if you need any help with your upcoming INDs!

Category: Regulatory Affairs, Drug Development Consulting

Keywords: IND, FDA, exempt

Other Posts You Might Like: